Guide: How to Plan for Microsoft Defender Endpoint Deployments and Migrations

When approaching a rollout of Microsoft Defender for Endpoint (MDE) for your organization, it can be difficult to know where to start. In my last article, MDE was explained at a high level: what it is and why you should care. This time, we will get into the weeds of how to actually plan for its usage.

Over the past few years, MDE’s scope has increased massively: it is now available in some form across not only Windows and Windows Server, but also macOS, iOS, Android and Linux server distributions. Feature availability differs between the operating systems, as do the tools available to deploy it and provide ongoing management. Many other vendor endpoint security platforms (referred to henceforth as third party) offer a single console that manages everything – installation, configuration, and response – and, while strides are being made to get there with MDE, you will have to know and navigate a few management systems, depending on the state of your environment.

In this article, we’ll try and simplify all you need to know about introducing MDE for your organization. You’ll learn about licensing, how it MDE differs between all those support platforms, the tools available for deployment and management, and a general strategy for replacing your existing solution with it. This is not a “click guide” and won’t hold your hand through every individual button and keystroke; the aim is to give you confidence in knowing how to get the ball rolling on your Defender for Endpoint journey.

Licensing

Like Office 365, Defender for Endpoint licensed users can use it on five devices. The service can be licensed on its own, but more commonly it is included in the E5 packages or their A5 equivalents. This includes Windows 10 Enterprise E5, Microsoft 365 E5, and the Microsoft 365 E5 Security add-on for Microsoft 365 E3.

The above covers end-user devices, but you also need to consider the server estate. MDE is included as part of Azure Defender for servers managed by Azure Security Center, or you can license it standalone with Microsoft Defender for Endpoint for Server (doesn’t that roll off the tongue?). That license, unlike the client license, doesn’t entitle you to five devices: it’s one license per server.

OS support and feature availability

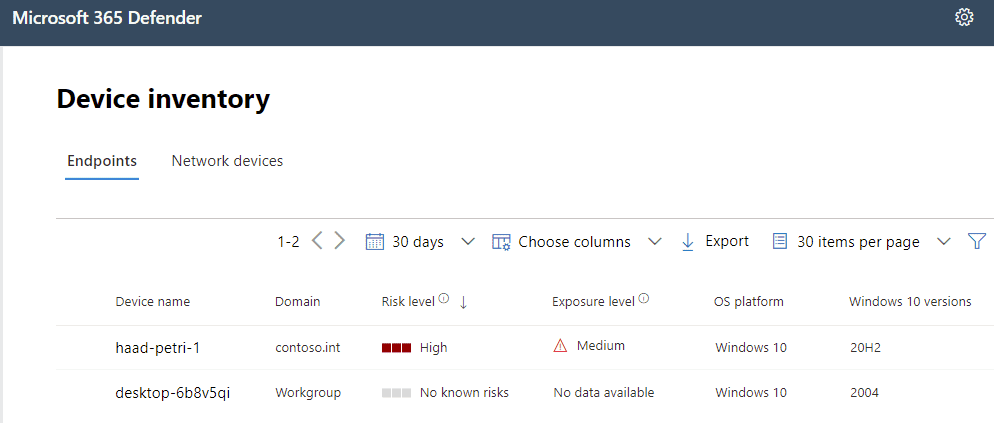

Getting a device into Microsoft Defender for Endpoint is referred to as onboarding. When onboarded, telemetry is gathered, the device becomes visible in Microsoft 365 Defender (security.microsoft.com) and, on supported systems, threats identified by the EDR system can be remediated or advanced features such as Live Response engaged. This is where things get a little intricate, and not always obvious. The onboarding process varies by OS, as do the endpoint detection and response (EDR) and advanced features available.

Let’s first look at Windows. On the client end of things, only Pro and Enterprise can be onboarded (no Home). In addition to Windows 10 (including Azure Virtual Desktop), you can onboard Windows 7 SP1 or Windows 8.1. Windows 10 is supported all the way from version 1607, but my recommendation is version 1803+, as that’s when the best features really start to open up, as we’ll get to.

Windows Server supports Long Term Servicing Channel (LTSC) versions 2008 R2 SP1, 2012 R2, 2016, and 2019. If using Semi-Annual Channel (SAC), you’ll need at least version 1803.

So that’s what’s supported for Windows, but they’re not all equal, and that’s because, as time has gone by, different components required by MDE have been built-in to the OS. Let’s explore that.

Think of MDE on clients as consisting of two key elements. First up, an endpoint protection platform or engine. This can scan files, remove them, implement policy, etc. This is the part of MDE that, crudely put, does a lot of the actual client-side work. Then there’s the EDR. This pipes all the telemetry and information about what’s going on with the endpoint back to the cloud service and using that large data set to power investigations, some post-incident remediation, threat detection beyond signatures and into behavior patterns, and populate databases that can be used for advanced hunting.

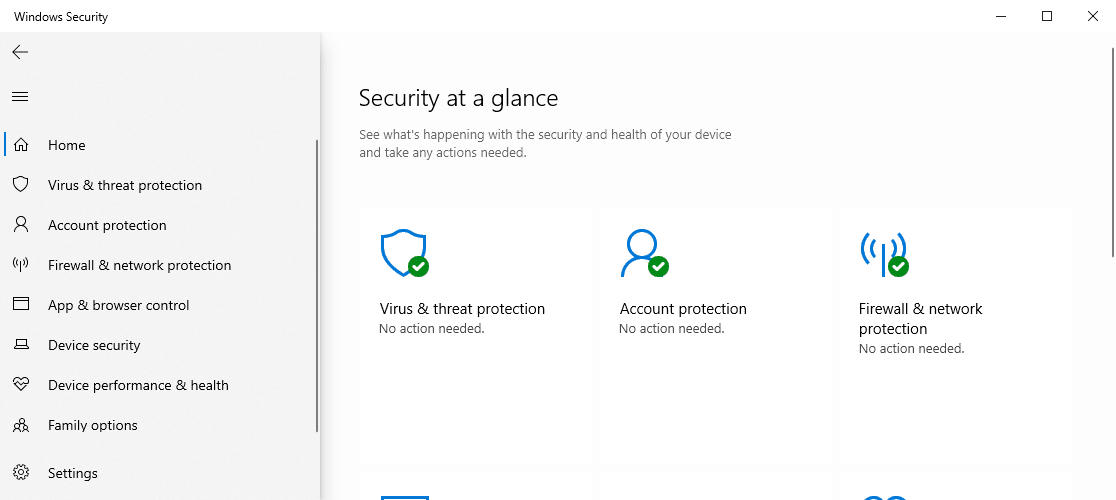

Windows 10 has had the EDR and engine – Microsoft Defender Antivirus (MDAV) – built-in; with MDAV exposed through the Windows Security app. But neither are native to Windows 7 and 8.1.

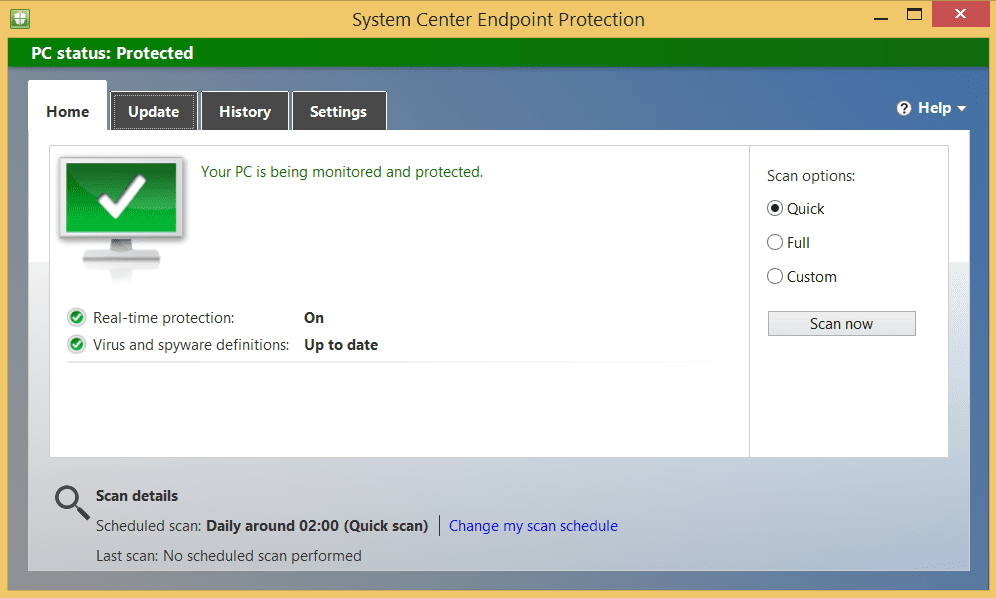

Instead of MDAV on these operating systems, you can deploy the System Center Endpoint Protection (SCEP) engine that comes with ConfigMgr. You don’t need to use ConfigMgr to deploy SCEP, it’s just that it originally was distributed with it. You can use Intune, Group Policy, or other software deployment tools.

For the EDR, you’ll deploy the Microsoft Monitoring Agent (MMA). Again, you can use basically any existing deployment tool to do this.

Over on Windows Server, we run into a similar problem, insofar as older versions have a mixed out-the-box configuration. Windows Server 2008 R2 and 2012 R2 will require SCEP and MMA; Windows Server 2016 requires only MMA as MDAV is built-in; and SAC version 1803 onwards or Windows Server 2019 doesn’t require anything extra. If running in Azure, instead of SCEP, you can use Microsoft Antimalware for Azure (MAA).

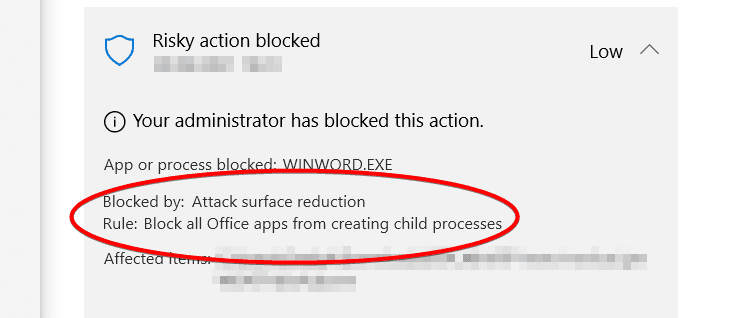

This mixture of tools to get different versions of Windows and Windows Server covered with a protection engine and EDR results in different features and protection parity. At the top of that list, one of the most compelling reasons for buying Defender for Endpoint – automated investigation and response (AIR) – is only supported on Windows 10 1709+ or Windows Server 2019. Indeed, you’ll need Windows 10 version 1709 (“Fall Creators Update”) at a minimum for a lot of features, as it’s with this version of Windows that exploit protection, network protection, and web protection were added, as were most attack surface reduction (ASR) rules. However, you’ll really want to set Windows 10 version 1803 as your baseline for endpoints running MDE, as that’s when block, at first sight, became available; a highly recommended service that uploads unrecognized files (based on worldwide hash details) to the cloud for analysis before allowing them to run.

All these cool features haven’t yet made their way to other platforms, though. Moving onto macOS and Linux, you won’t find AIR, exploit/network/web protection, ASR rules, or block at first sight. Firewall capabilities are also limited to only Windows.

macOS has rolling support for the three major versions which, currently, means 10.14 (Mojave) to 11 (Big Sur), however, the new M1 chips aren’t supported yet. Feature-wise, you’ll get alerts and investigations, threat and vulnerability management, and a preventative antivirus; but no options dependent on Microsoft Defender Antivirus such as web content filtering or AIR. The same is true of Linux, which supports some server (but not consumer) distros: RHEL and CentOS 7.2, Ubuntu 16.04 LTS, Debian 9, SUSE Enterprise 12, and Oracle 7.2.

Lastly, for platform support, we have mobile operating systems iOS/iPadOS and Android (mobiles only). Given these devices are radically different from traditional desktops, their feature set is too. Both offer a loopback VPN, which protects email, web, and other traffic from phishing campaigns. Both can also support Intune mobile application management (MAM) policies to feedback device risk to control access rights. On Android, you’ll be able to scan for malicious or potentially unwanted apps (PUAs). Microsoft Tunnel is a new service making its way to both, too, with a little variance between systems, which tunnels traffic from mobiles to on-premises resources.

As Defender for Endpoint has seen relentless investment, its feature set has grown and grown, with different devices getting those features at different rates; newer versions of Windows 10 understandably getting them sooner. The key takeaway is that onboarding into MDE provides EDR alerts, incidents, and telemetry for all platforms, and then you have separate endpoint engines to deploy with differences in features between platforms. I am working on a matrix of supported features by OS – something Microsoft only really supply across a mountain of different documentation pages – and hope to release it soon.

Onboarding and deployment paths

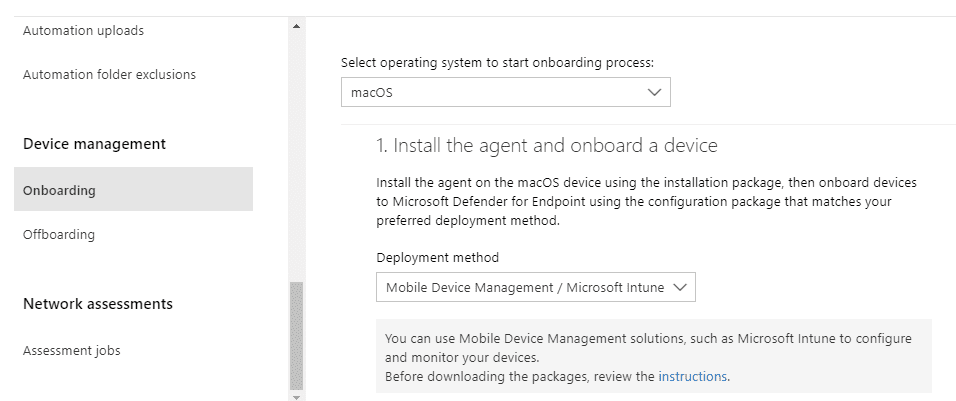

Although you cannot actually deploy MDE from the Microsoft 365 Defender security portal, there is a settings page that provides clear guidance on how to proceed based on the tools in your arsenals, such as MDM or orchestration.

All platforms supported by MDE support manual deployments such as running a script or deploying an app. For devices fully enrolled in Intune such as Windows 10, macOS, Android, and iOS, you can use that as your deployment tool; and if you only use MAM on Android and iOS, that’s supported too by users manually installing the app from the store.

If MDM isn’t an option, Group Policy can also be used, as can System Center Configuration Manager 2012 or later. My general advice, though, is to use your MDE deployment as a larger project to also Intune enroll your devices (or Jamf for macOS). This can be done using Configuration Manager co-management or Group Policy-invoked automatic enrolment. For servers or downlevel devices that cannot be Intune enrolled, however, you can also use tools like Group Policy and ConfigMgr to deploy the engine apps such as Microsoft Monitoring Agent or SCEP (discussed earlier).

Linux server deployments can be supported through orchestration tools such as Puppet and Ansible, which brings us onto the Azure Defender option. Azure Defender is a separately licensed service for your Azure environment that includes Microsoft Defender for Endpoint. It doesn’t yet onboard Linux, but that’s on the roadmap. Where things get really cool, is that you can extend Azure Defender beyond servers hosted in Azure if they are configured as such with Azure Arc.

Azure Defender’s MDE integration extends to Azure Virtual Desktop. If you have on-premises or alternative VDI environments, that non-persistent virtual desktop infrastructure can be onboarded too by using a combination of Group Policy and a configuration package for your golden image.

Dealing with your existing endpoint protection

It’s a trope at this point in project management, but you can’t put enough effort into planning the deployment. Now that you know the platforms supported and their feature level, consider which you’re going to onboard and what tools you have in order to do so. Think about who needs access to those tools and how they can get it with only enough permissions to get the job of the migration done. Test fundamentals, such as network connectivity to Microsoft cloud services. Consider your pilot group of devices and users too. Ideally, you don’t want to “big bang” this migration. Most organizations start with the IT team, then expand the scope from department to department or location to location.

IT life would be so much simpler if always deploying to greenfield environments but, alas, you’ll probably have an existing third-party security solution in place that you need to migrate to Microsoft Defender for Endpoint. How does that factor into things?

Let’s again think about the two areas of concern on the client: the engine, and the EDR.

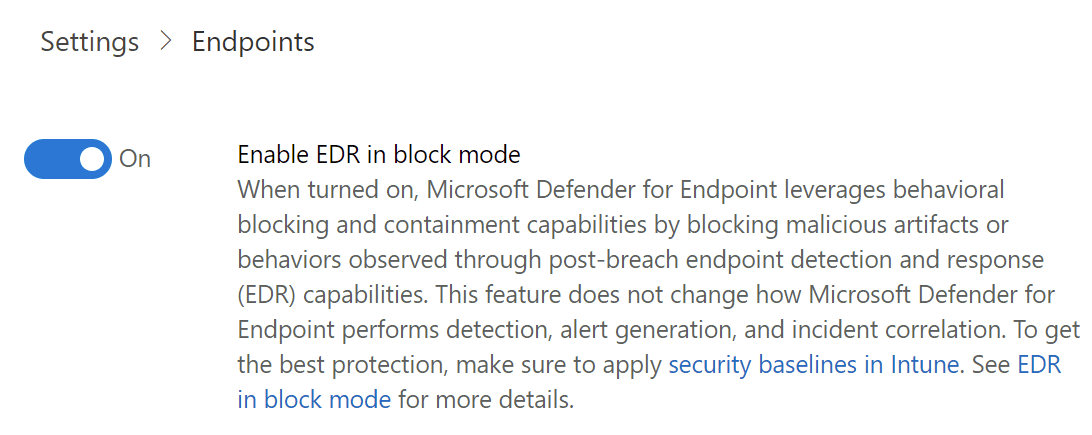

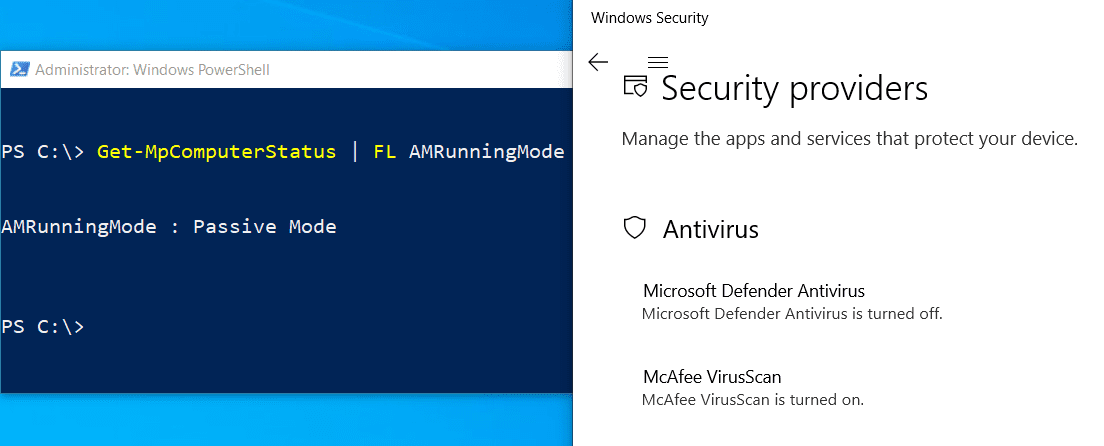

It’s the engine you probably already have covered by a third party such as Sophos, McAfee or Symantec – the usual suspects. The good news is you can still onboard the EDR element with that running. This means you have a third-party engine running alongside Microsoft Defender for Endpoint for EDR. On supported platforms, you can even enable a feature called EDR in block mode which can provide post-incident remediation if the third party didn’t. So take that as step one in the actual deployment: onboard devices into EDR.

What about the process of actually getting rid of the old software? You don’t want to keep paying for that third-party antimalware engine when you’re now licensed for the Microsoft equivalent. Additionally, you want to minimize any duration of transition or period without an active antimalware engine. As you’ll expect from the earlier discussion on OS differences, our options here will differ by OS too.

After onboarding, Windows 10, Server SAC 1803, and 2019 support the ability for Microsoft Defender Antivirus (remember – that’s the engine) to enter automatic passive mode (2016 can do it, but not automatically). This happens when a third-party engine is detected and sees Defender Antivirus hand over remediation capabilities to that third party. Then, as soon as your old solution is uninstalled, it enters active mode, which does what it says on the tin. The great thing about this capability is you don’t need to juggle or manage the switch over. You simply plan your uninstallation of the old system, and Defender Antivirus takes over.

Other platforms don’t support this as they don’t have Defender Antivirus built-in. On those, I like using custom scripts that will, in one swoop, uninstall the existing solution and install the appropriate engine, such as SCEP, or the Defender for Endpoint app on macOS and Linux.

A common configuration made prior to deployments is to make exclusions in your existing system and include them in Defender for Endpoint. While this isn’t the worst thing you could do, the recommendation is to see how things go with your pilot in the first instance. Exclusions pose an attack surface, which we want to minimize; so start from scratch if possible. It’s also common to exclude Defender for Endpoint processes and services from your existing solution, which is particularly common if operating in EDR in block mode.

What’s next?

That’s a lot to take in!

As you’ll have discerned from the all above, this is a big project, with a lot of intricacies as soon as you start working with different platforms. However, now you’ll understand what you can get out of Defender for Endpoint, and the approach to getting it, based on your own individual circumstances. By this point, your devices are onboarded into the service, and the antimalware engine is no longer a third party.

Getting devices into the service is just the beginning. There are endpoint security settings to be configured, and important service-side settings and features you need to know about and manage. In the next article in this Defender for Endpoint series, we’ll get into those so you can harden, protect, and monitor your environment effectively.

Related articles: