Office 365 Has Changed Enormously Since 2011

The Unlovable Nature of BPOS

At the start of the decade, Microsoft’s cloud offering was the deservedly maligned Business Online Productivity Services (BPOS: a name only its inventor could love). BPOS was unreliable and didn’t work particularly well. Because BPOS used software designed for on-premises use, it struggled to cope with cloud operations.

Thankfully, Microsoft transformed its cloud office system with the introduction of Office 365 on 28 June 2011. After a slow start, Office 365 has gathered pace and overcome G Suite, its major rival to become the leader in cloud office systems. In this article, I look back at the roots of Office 365 and discuss the three major issues that initially spooked customers about the cloud. In the next, I describe some of the Office 365 successes and failures in the last decade.

From Limited Beginnings

Looking back from today’s perspective, it’s hard to remember just how limited Office 365 was in 2011. The software was based on the 2010 on-premises versions of Exchange, SharePoint, and Lync knitted together with a licensing and administration portal. Microsoft’s engineering groups were still working out how to transform the on-premises software to work at cloud scale, and it’s fair to say that this process didn’t finish until a few years later.

The Office 365 ecosystem also needed to be built out. Where Microsoft had three datacenter regions in 2011, it now delivers Office 365 services from 17, a development that resolved the initial fears some customers had about data sovereignty. The datacenters are connected by a dark fiber network linked to a huge set of local connection points to make it easy for users to work no matter where they are. Tenants can run a multi-geo configuration for Exchange Online, SharePoint Online, and OneDrive for Business, and Microsoft is steadily moving app data closer to customers as it builds out its datacenters.

The Office 365 datacenters store enormous amounts of user data. Microsoft has increased quotas for Exchange Online and SharePoint Online (for instance, the standard enterprise mailbox is now 100 GB instead of 25 GB) and many ISVs make products to help customers move data from on-premises apps into the cloud. We’re now at the point where the majority of Exchange and SharePoint activity is cloud-based, and the number of on-premises customers for Office servers continues to fall year over year.

Office 365 Plans

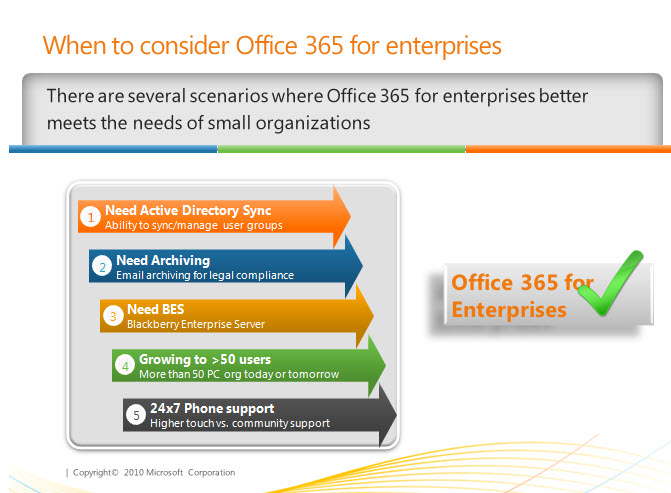

At launch, Microsoft offered Office 365 plans for kiosk (now frontline) and enterprise workers. A set of slides posted by Mary-Jo Foley includes how Microsoft positioned Office 365 enterprise (Figure 1) when they started to talk to customers about the new cloud office suite.

The Price of Office 365

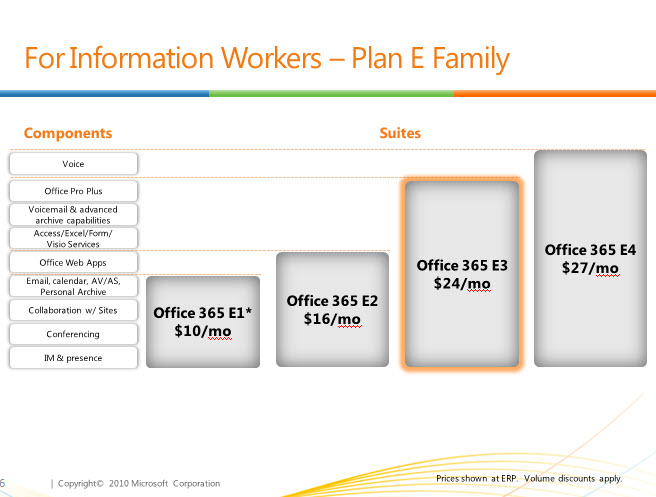

Access to Blackberry Enterprise Server was important in 2011, but the list of advantages Microsoft touted for Office 365 was short (possibly because no one realizes how good cloud office could be then). What’s interesting is the pricing Microsoft set for Office 365 (Figure 2). Plan E3 was $24/month then, and it’s $20/month now.

The point here is that companies were scared that Microsoft would get them onto Office 365 and then hike the prices, something that simply hasn’t happened. In fact, Office 365 is a relative bargain now because all its plans include more and better functionality than they did in 2011.

Instead of bumping plan prices up, Microsoft has concentrated on growing the numbers of Office 365 accounts and increasing the Average Revenue Per User (APRU) by upselling add-ons and higher-priced plans to customers or moving them to Microsoft 365. Office 365 now has over 200 million monthly active users and has grown at between 3 and 4 million users per month since 2015 and Office 365 is responsible for the bulk of Microsoft’s cloud revenues, so their tactics have worked.

Office 365 Availability

Being price-gouged was one customer fear in 2011. Not trusting cloud services to deliver highly available services was another. Microsoft launched Office 365 with a financially-backed guarantee that the 99.9% Service Level Agreement (SLA) would be reached. Since then, Microsoft hasn’t had to pay out all that often. In fact, I can only remember one instance in September 2011 when the infrastructure was still maturing, and Microsoft’s automated datacenter management processes were not as extensive or as tightly controlled as they are today.

Given the size of Office 365, it’s inevitable that something is going wrong at any time you care to look. But the number of tenants, distribution across multiple regions, and the way the software is deployed and managed mean that it’s a rare incident that comes anywhere close to budging the SLA needle (an example of one that did is the MFA outages in 2018). This has been the case for several years, which begs the question whether the Office 365 SLA is relevant today.

Security and the Cloud

A perceived lack of security was the last of the triple whammy used to justify not going to the cloud. When you think about it, this is a laughable notion for most organizations because they don’t possess the experience, knowledge, skills, and resources that Microsoft dedicates to protecting Office 365 against a world of threat. Microsoft says that 3,500 security professionals protect customer data, all of whom probably know more about security than I do. I lost the fear of having my data in the cloud a long time ago and like the idea that dedicated personnel are responsible for protecting the service.

Attacks happen all the time, but I can’t recall reports of any Office 365 tenant being penetrated solely because of a Microsoft failure. Maybe no-one highlights big security breaches because they do not want to embarrass their company, or I am just not listening. In whatever case, it’s still true that the responsibility for basic security remains with tenants. In this respect, the low percentage of sensitive Office 365 accounts protected with multi-factor authentication is an ongoing scandal.

Moving into a new Decade of Cloud Office

Microsoft’s commercial cloud products have grown to an annual revenue run rate of well over $40 billion. Office 365 is a big part of that success. To its credit, Microsoft has overcome many technical, organizational, and business challenges to attain that success. The trick now is to keep customers happy, ahead of the competition, and deliver the same quality of service over the next decade.