Working with PowerShell Variables

- Blog

- PowerShell

- Post

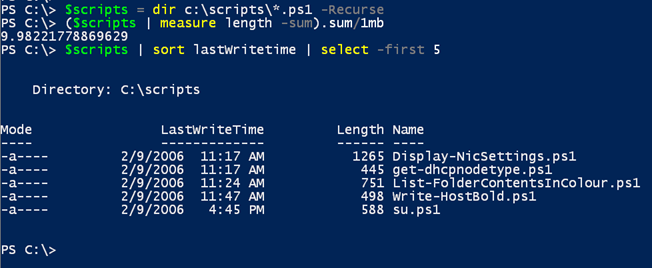

In a previous article, I introduced you to PowerShell variables. With variables, you can easily define a variable to store a piece of information or to hold the contents of a command. This latter idea is very important. If you have a PowerShell expression that takes a bit of time to run, and you want to try different things with the results, you don’t want to be re-running the command. Instead, define a variable.

- Related: Introduction to PowerShell Variables

$Scripts = dir c:\scripts\*.ps1 –Recurse

Now I can use the variable, Scripts, as much as I want without having to re-run the directory listing.

As you can see, there’s nothing magical about defining a variable. You can change the value simply by assigning a new value.

$scripts = dir c:\scripts\ -Recurse –file

This is why I suggest using meaningful variable names instead of something like X or VAR. On a related note, you can also run into situations like this where you tell PowerShell to turn something into a specific type of object.

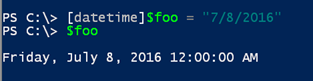

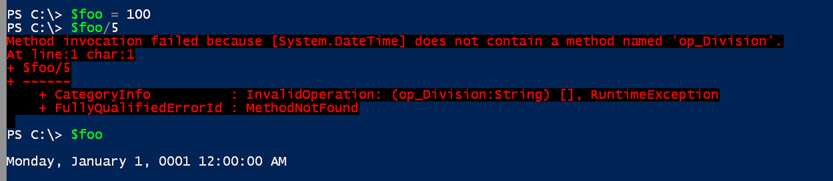

I’ve defined the variable foo to create a datetime object. Later on in the day, I might try to re-use that name like this and get an error:

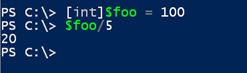

What happened is that you told PowerShell that you wanted whatever you put into $Foo to be treated as a datetime object. You may have completely forgotten that you defined $foo earlier in your session. If you’re like me and keep a PowerShell session open for days at a time, then your easiest solution is to assign a new type:

You can also remove the variable completely, which I’ll cover in a moment.

Variable cmdlets

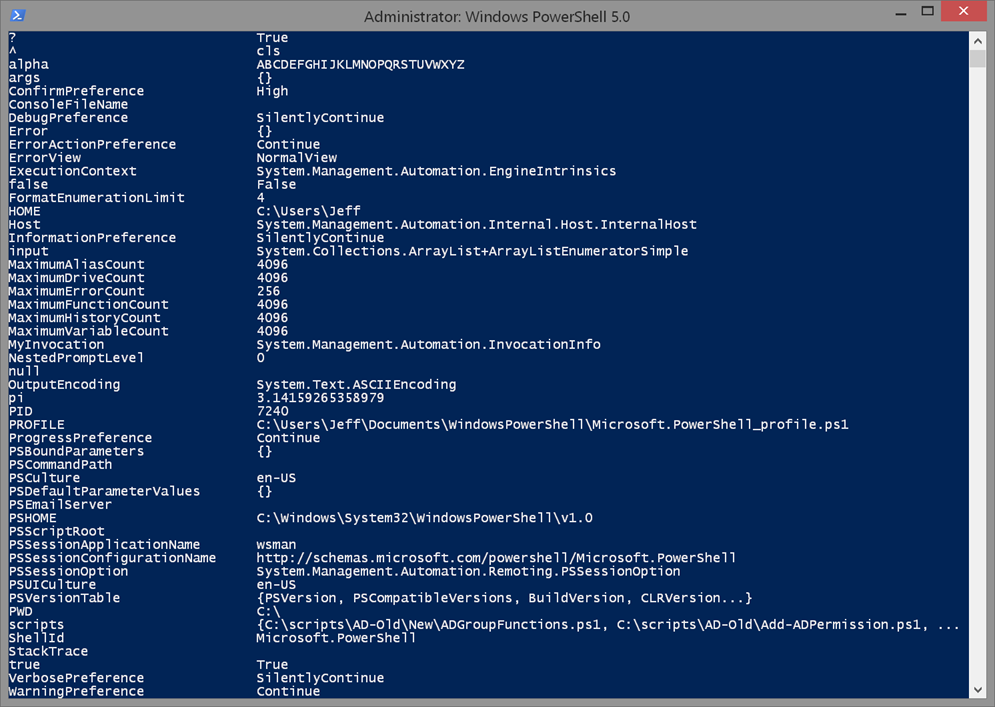

If you need to keep track of what variables you’ve defined, you can use the Get-Variable cmdlet. Remember, variables only exist for as long as your PowerShell session is running. Once you close PowerShell, the variables go away.

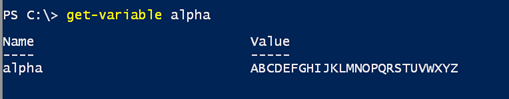

Many of these variables are created automatically by PowerShell. You can also select a single variable.

Note that you don’t include the $ sign with the name. But I can see that there’s a value. This is a handy way of checking if a variable is already in use. You can then decide if you want to change it.

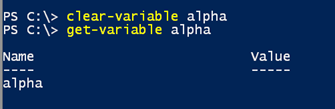

As I mentioned a moment ago, variables only exist for as long as PowerShell is running, so typically we don’t worry about cleaning them up. In a script, however, you might want to clean up variables to avoid accidentally re-using a variable. In these situations, you can use the Clear-Variable or Remove-Variable cmdlets. The former will retain the cmdlet, but wipe out the value.

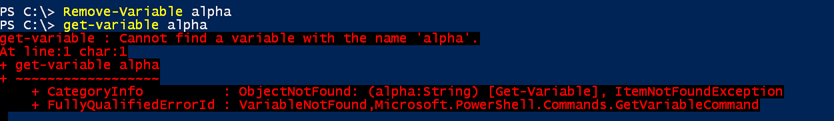

The latter will completely remove the variable.

In my problem example earlier with the variable $Foo, I could also remove Foo and start all over again.

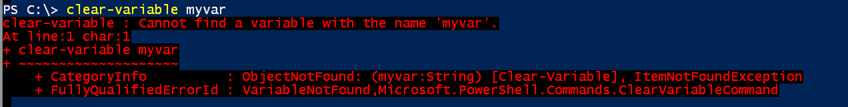

Again, note that in all cases we use the variable name without the $. If you attempt to remove or clear a variable that doesn’t exist, PowerShell will complain.

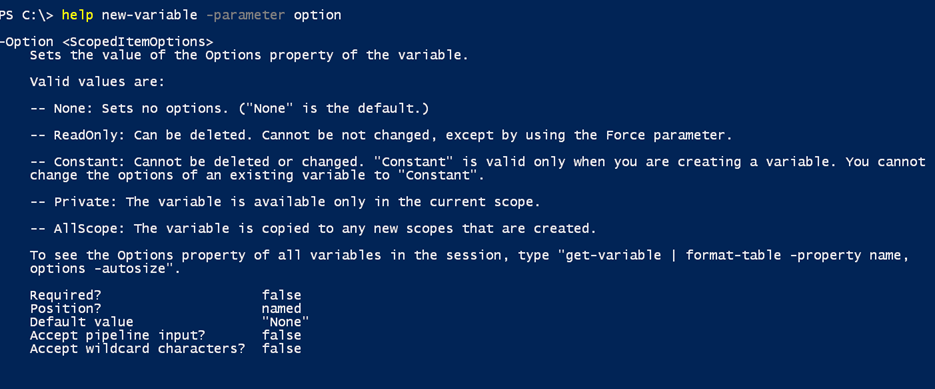

One last feature with variables you might want to consider is defining them up front with the New-Variable cmdlet. The primary reason would be to take advantage of the Option parameter. This is the only way you can create protected variables.

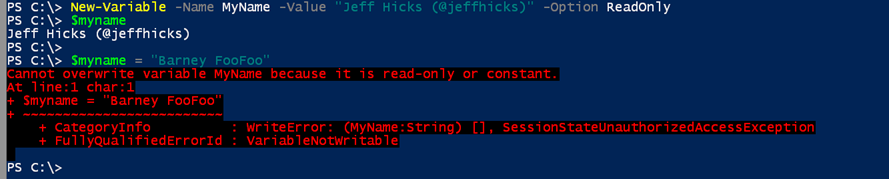

I have a number of variables defined in my PowerShell profile scripts that are flagged as ReadOnly, so that I don’t accidentally change them. When you create a ReadOnly or Constant variable, PowerShell will complain if you try to change it.

I expect you will use variables frequently and not think too much about it. There are only a few things to watch out for, and if you use a little common sense, then you’ll rarely encounter problems. But if you have, I’d love to hear about it.