Teams at Home Might Not Convince Potential Users

Melding Teams at Work with Your Personal Life

On June 22, Microsoft launched the preview of the much-awaited consumer iteration of Teams, which you can access through the Teams iOS and Android apps. Microsoft’s hope is that the millions of people who use Teams at work will make the leap to embrace Teams for their personal life through chats, sharing files, organizing events in the calendar, and tasks.

Adding the Personal Touch

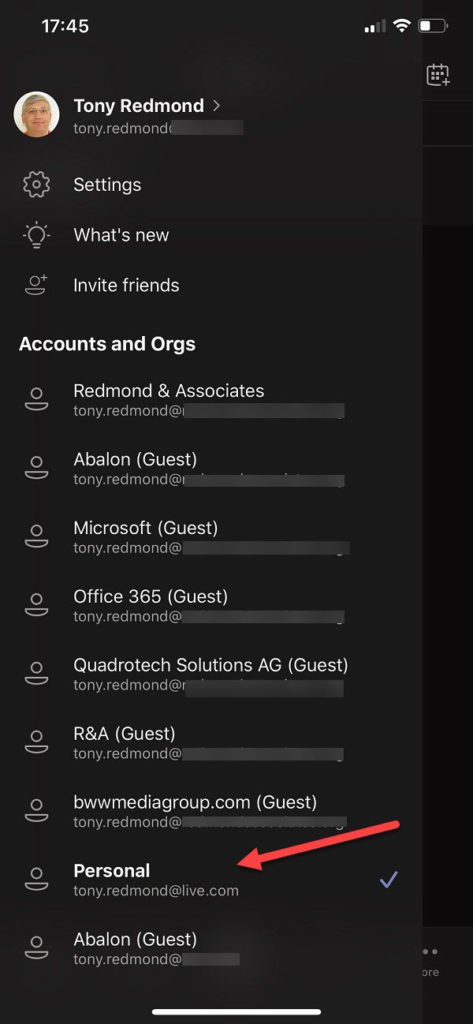

If you’ve used the Teams mobile app before, Teams at Home won’t be a difficult learning curve. After adding a personal account using an email address that isn’t associated with an Office 365 tenant), Teams creates an entry for an organization called Personal (Figure 1). The process is very easy if you already have a Microsoft Services Account (MSA), such as one with a live.com or outlook.com address. If you don’t, Teams creates an MSA for you. You can then switch between Teams at work (all the Office 365 tenants you use with Teams, including those where you have a guest account) and Personal.

Under the surface, Microsoft has done a lot of work to make the single Teams client deal with the complexities of switching between personal and work. The complexities include handling different authentication mechanisms (Azure AD and MSA), making sure that notifications for new activity are surfaced correctly no matter how many tenants you connect to, and so on.

Much the same Layout

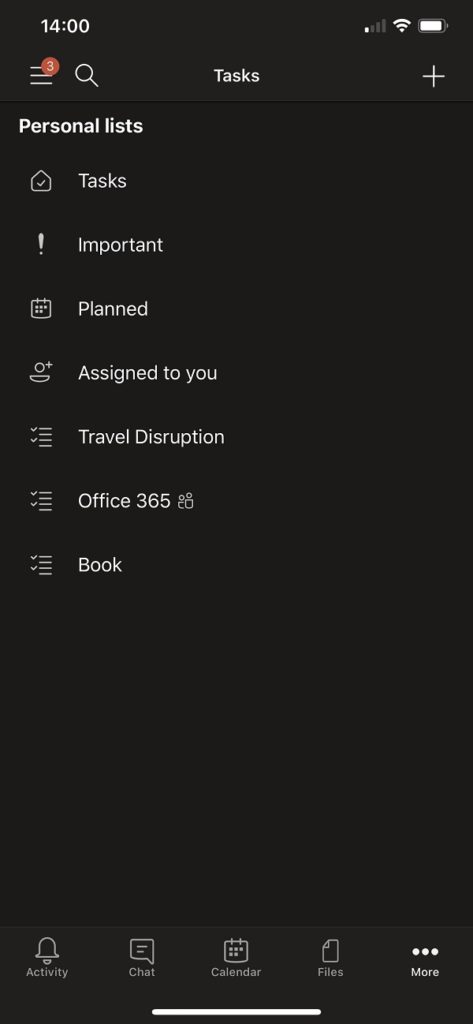

Everything in the Teams mobile client looks like Teams at Work even if the technical underpinnings are different. Figure 2 shows the Tasks section of Teams when connected to Teams at Home. The data here comes from the user’s personal To Do account.

The only problem I’ve had switching between work and personal accounts is when Teams at Home decided that it didn’t want to switch back to Teams at Work. No amount of prodding would convince the client to switch until I rebooted my iPhone. It’s a preview, glitches are expected, and an update to the iOS client seems to have solved the problem.

Comparing Teams at Home and Teams at Work

In March 2018, before Microsoft launched the free version of Teams, I speculated how the technical underpinnings of the free version would operate. I was wrong in those details because the free version of Teams is much closer to the enterprise version to make it easier for Microsoft to convert a free tenant into a paying tenant.

But many of the points I made then appear in Teams at home. For example, Outlook.com replaces Exchange (not a big problem because both services share the same infrastructure) for email and calendar services, while OneDrive consumer is used for file storage and sharing. The calling and meeting functionality of Teams is based on the same media stack as the Skype consumer service and works in the same way in both versions, with the exception that some of the add-on features delivered by Stream (like recordings of Teams calls and transcript generation) aren’t available.

Table 1 summarizes the differences between the enterprise and personal versions of Teams.

| Feature | Teams at Work | Teams at Home |

| Personal Chats | Yes | Yes |

| Group Chats | Yes | Yes |

| Video and Audio Calls/Meetings | Yes | Yes |

| Channels | Yes | No |

| Personal file storage | OneDrive for Business | OneDrive consumer |

| Shared file storage | SharePoint Online | None |

| Calendar | Exchange (online/hybrid) | Outlook.com |

| Email (for notifications, invitations) | Exchange (online/hybrid) | Outlook.com |

| Tasks | To Do (work) and Planner | To Do (personal) |

| App extensibility | First (Microsoft) and third-party apps | TBD |

| Authentication | Azure AD | Microsoft Services |

| Store items securely | N/A | Safe |

Table 1: Comparing Teams at work and Teams at home

As you can see, channels (public or private) aren’t available in Teams at home. Instead, conversations are organized into personal or group chats, which work as they do in the enterprise version.

Teams at Home, Invitations, and Clients

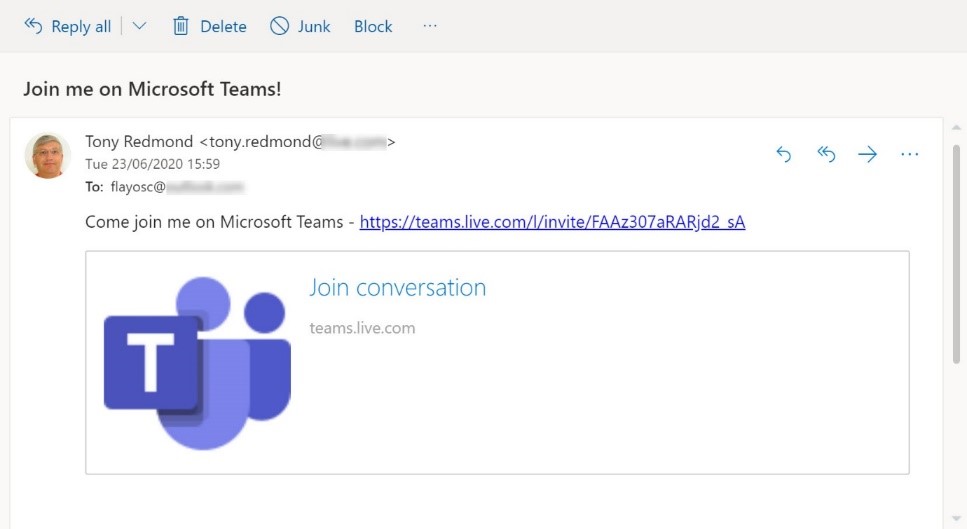

Teams for home uses a different endpoint (teams.live.com) to the enterprise version (teams.microsoft.com). For now, only mobile clients are supported. You expect seams to show in previews, and this is where the biggest unfinished piece is obvious. You can invite someone to join you in Teams at home by creating an invitation sent to their email address (Figure 3).

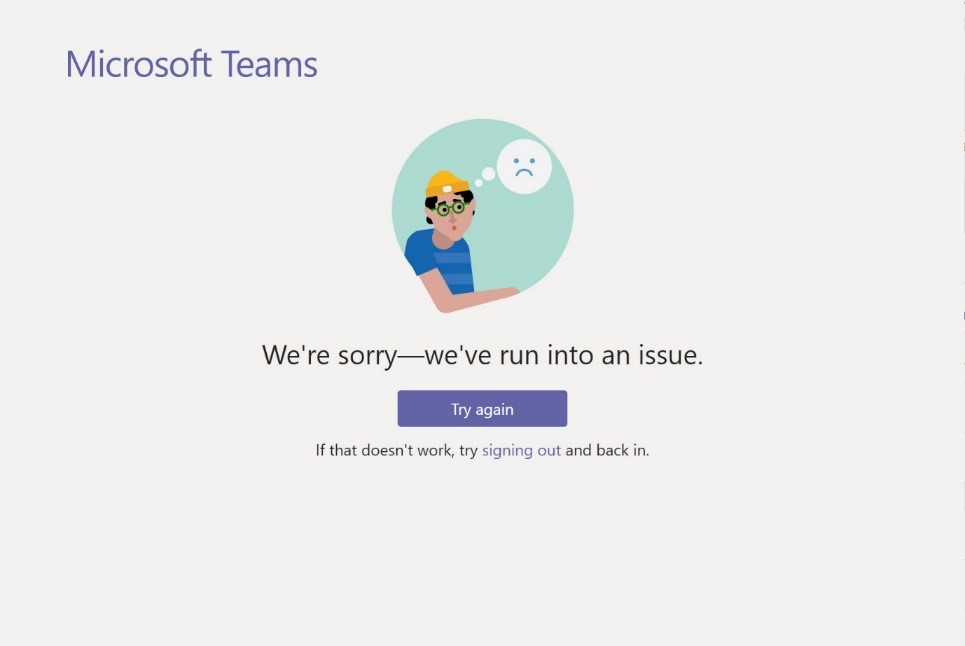

They might read the email in a browser or desktop client and click the link (or deeplink, because it holds instructions about how to redeem the invitation). After signing in (and providing a telephone number), the user lands on a browser page to choose whether to open the app or use the browser client. Neither works because Teams.live.com only supports connections from mobile clients right now (Figure 4).

Microsoft will address the issue and make it possible to use browser and desktop clients with Teams at home, but for now it’s a frustrating gap, especially as no instructions are in the email to say that invitations can only be accepted on a mobile device.

Another frustrating point about the joining experience is that Teams at home insists that everyone has a unique phone number in addition to their email address (also unique). I’m assuming that this is laying the foundation for a future merge with Kaizala, a topic that Microsoft has been silent about since its last communication in June 2019.

The Acid Test for Teams at Home

The Acid test is whether Teams at Home can replace other ways people have of organizing their daily life. My family consists of adults, so we’re probably a good test case. After several days of trying to use Teams at Home, the outcome wasn’t what Microsoft would hope. All deemed WhatsApp groups are easier to use than Teams; this was despite two of my three children having experience of Teams in work (the other uses Slack).

A major hurdle is that although people who use Teams at work are likely to have the Teams mobile client already installed on their device, others in their family probably don’t. It’s more likely that the other family members and contacts use WhatsApp or Facebook or Skype, so asking the non-Teams users to download and use a new app “to organize the family” goes down as well as the proverbial lead balloon. The point is that everyone has the other apps, so why switch? This is where Microsoft might be trying to push water uphill.

Not Compelling Enough

Convincing people that it’s worthwhile to move to Teams to organize their lives is the core challenge Microsoft faces. Although attractive to Teams fans, Teams at home isn’t yet compelling enough for others to embrace. But hey, it’s a preview, and things change before general availability, so it’s always possible that Microsoft will dramatically overhaul the app before then. Isn’t it?