How Secure is Video Conferencing App Zoom?

- Blog

- Compliance

- Post

There’s been a lot written in the press recently about video conferencing app Zoom. From claiming that it is malware to more detailed analysis of its security, or lack or security in most cases. The app has seen a large increase in use over the past weeks as the worldwide coronavirus pandemic has forced many to work from home. VentureBeat reported early in April that daily active users rose from 10 million to more than 200 million in just three months.

Many news outlets have reported on Zoom’s security failings. With the Guardian going as far to say that the software was ‘malware’. The article describes issues such as Zoom-bombing, where hackers interrupt online meetings. And it goes on to say that despite Zoom’s initial claims, end-to-end encryption is not used to secure calls, so that they can only be decrypted by participating users.

MacOS Zoom vulnerabilities

MacOS has been particularly affected by Zoom’s security woes. Ex NSA hacker Patrick Wardle revealed two zero-days at the end of March. The first can be used by a local attacker to get access to the root account in MacOS. The second involves code injection to get access to the microphone and webcam without alerting the user.

But while Zoom is currently in the spotlight, this isn’t the first time the app has come under scrutiny. Last year, Zoom was found to be silently installing a hidden webserver on MacOS so users could be added to calls without their permission. And at the end of March, Zoom plugged a well-publicized problem in its iOS app that was sending analytics data to Facebook.

A closer look at Zoom security

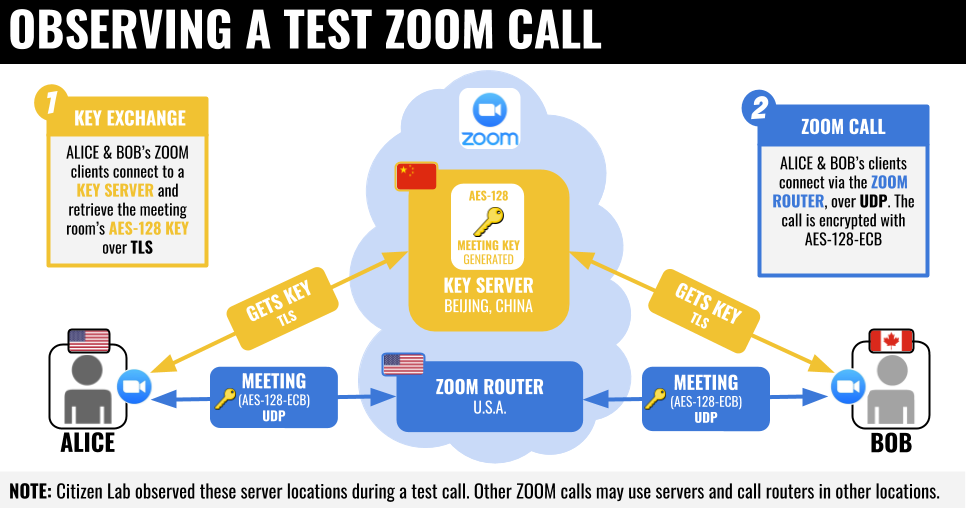

The University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab has posted a more detailed look at how Zoom calls are secured. While Zoom doesn’t employ end-to-end encryption, it does encrypt data in transit. Zoom’s documentation claims that it uses Transport Layer Security (TLS) version 1.2. But Citizen Lab was unable to confirm that. Furthermore, Zoom apparently uses its own encryption method in a modified version of the Real-Time Transport Protocol (RTP), which is used for streaming audio and video.

A single AES-128 key is used by all call participants to encrypt and decrypt video and audio streams. But the mode of operation is Electronic Codebook (ECB), which leaves patterns in the input, potentially allowing an attacker to obtain the contents of a call, albeit in poor quality.

The AES-128 key used for a call can be used to decrypt Zoom packets if they are intercepted. The keys are likely generated by Zoom servers, and sometimes delivered to call participants, using servers located in China. Regardless of where call participants are located. Although Citizen Lab did also find 68 servers located in the U.S. that appear to run the same software as the servers in China.

While Zoom is registered in the U.S., Citizen Lab says that it appears to own three companies in China that employee around 700 people to develop the software. That could leave users vulnerable if the Chinese government demanded the companies hand over encryption keys stored on servers in China.

Poorly implemented Zoom features

Hackers have been able to ‘Zoom-bomb’ meetings because the software allows participants to join using a simple URL containing a string of 9 to 10 numbers that can be easily guessed or generated. Citizen Lab also found an issue in the Waiting Room feature. Waiting Rooms are virtual spaces where participants wait until the host starts the meeting. Details of the vulnerability have not been released to give Zoom a chance to address the problem.

Should I use Zoom?

As Citizen Lab points out, if you are using the platform to conduct meetings that might normally happen in a public space, then you might consider Zoom’s lax security to be a non-issue. If you do decide to use Zoom, you should avoid the Waiting Rooms feature and enable passwords for your meetings to help prevent Zoom-bombing.

If you need a platform with security that can reasonably provide strong privacy and confidentiality, then Zoom is not the solution for you. At least as it stands in its current form. Microsoft Teams doesn’t use end-to-end encryption either. But it was designed with security baked in from the get-go. And a lot depends on how much you trust Microsoft, or other solution provider, with the keys used to encrypt and decrypt communications.

You can find an overview of security and compliance in Teams on Microsoft’s website here. And you can see Zoom’s response to Citizen Lab’s research here.