Exchange Online PowerShell Goes RESTful – But Only for Some Cmdlets

Slow and Painful Moving to Faster and More Reliable

Exchange 2010 introduced remote PowerShell (RPS) as the basis for Exchange server management. A decade later, we’re still using the same kind of technology to run cmdlets against Exchange cloud and on-premises servers. Remote PowerShell is OK for small to medium organizations, but it runs out of steam when exposed to the scale of the cloud. Scripts take hours to run, cmdlets sometimes fail to complete, and extensive error handling is needed to make sure that any session disconnects are handled properly. In short, Exchange Online PowerShell can be messy.

New RESTful Cmdlets

The good news is that Microsoft has a project to take a new approach to Exchange Online PowerShell. Announced at the Microsoft Ignite 2019 conference in Orlando, Microsoft is building a set of new REST-based cmdlets that are much faster and more reliable. The new cmdlets are now available in a private preview with general availability expected in early 2020.

The bad news is that only nine of the 700+ cmdlets in the Exchange Online PowerShell module have been upgraded to date. More are coming, but it takes time for the transition to complete. Microsoft chose the target cmdlets very deliberately. After analyzing the most popular (heavily used) cmdlets and the ones that experienced most problems at scale, Microsoft prioritized this set of RPS cmdlets as upgrade targets:

- Get-Mailbox.

- Get-CASMailbox.

- Get-Recipient.

- Get-RecipientPermission

- Get-MailboxPermission..

- Get-MailboxFolderPermission.

- Get-MailboxStatistics.

- Get-MailboxFolderStatistics.

- Get-MobileDeviceStatistics.

The REST-based version of these cmdlets are prefixes with Get-Exo, so you end up with Get-ExoMailbox, Get-ExoRecipient, and so on. The new cmdlets are now available when you connect a PowerShell session to the Exchange Online Management endpoint (see below).

You’ll notice that the chosen cmdlets all fetch data. That’s because problems most commonly happen when scripts fetch large quantities of data (for example, information for 50,000 mailboxes) for processing. Updating an object like a mailbox or permission is a focused transaction; grabbing large sets of objects takes time and is prone to failure due to server or network problems.

More Cmdlets in the Pipeline

Microsoft says that they’re considering upgrading other cmdlets. However, they can’t yet say what cmdlets are suitable candidates for upgrade or when more might be available.

Speed and Feeds

The REST-based cmdlets are stateless and have no affinity to a specific Exchange server. If a network problem affects a connection, the cmdlet can disconnect and connect to resume processing seamlessly with in-built support for retries following errors and the ability to resume from points of failure. In addition, Microsoft has taken a hard look at how the cmdlets access Azure Active Directory to make calls more efficient. There’s a fair amount of history here because Exchange has traditionally been liberal in how it allows objects to be found using anything from an alias to the old X.500-based distinguished name.

Another performance tip is to reduce the set of properties returned for objects to a minimum; if you want other (potentially expensive) properties you can ask for them and take the performance hit.

Installing and Running the REST cmdlets

To install the REST cmdlets, open an administrator PowerShell session and run this command:

Install-Module ExchangeOnlineManagement

Here’s the link to the module in the PowerShell gallery.

After the module is installed, you should be able to run the Get-Command cmdlet to find that the set of Get-EXO cmdlets are available:

Get-Command Get-Exo*

You can then connect to the module and authenticate with the Exchange Online management endpoint to load both the REST and RPS cmdlets with:

Connect-ExchangeOnline

To connect with a single sign on, specify your user principal name:

Connect-ExchangeOnline -UserPrincipalName [email protected]

Performance Testing

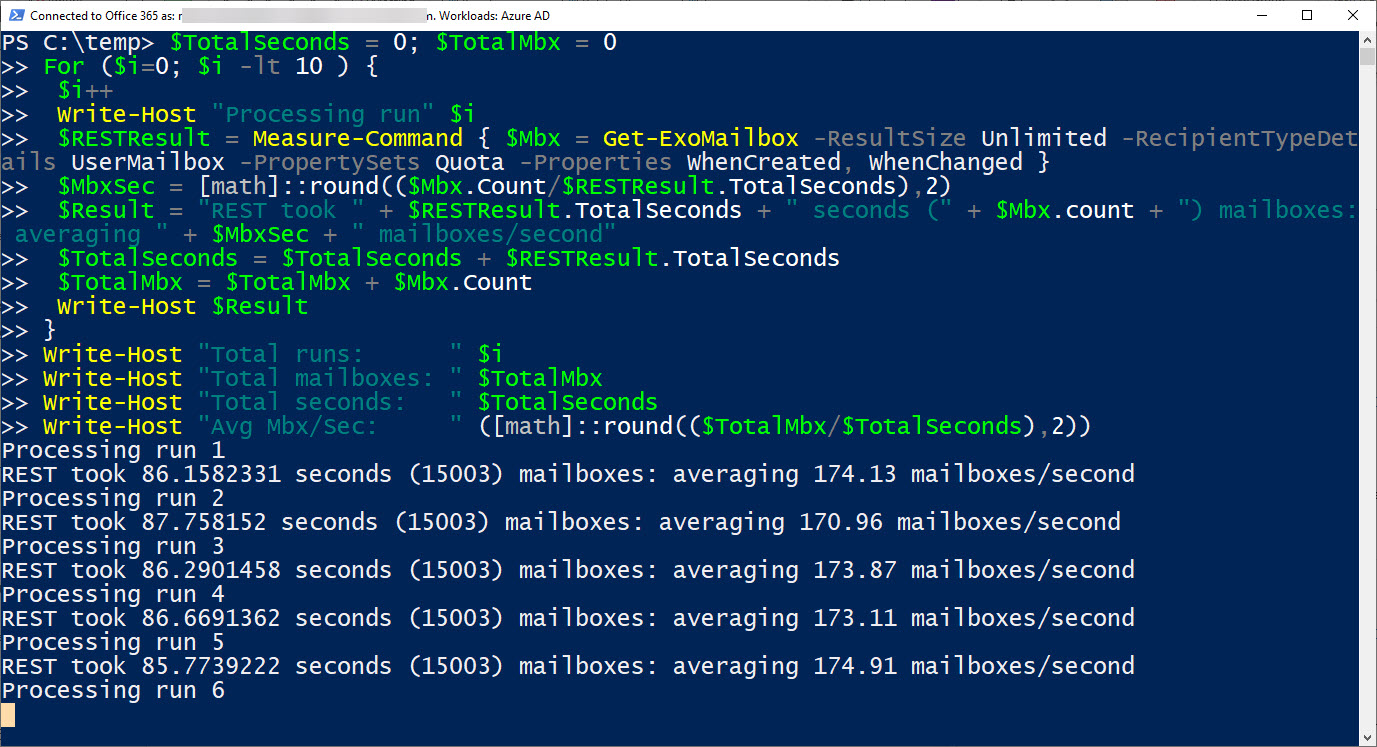

To see how the new cmdlets performed, I created a script to fetch 15,003 mailboxes with Get-Mailbox and Get-ExoMailbox and checked the elapsed time with Measure-Command. Here’s the script:

$TotalSeconds = 0; $TotalMbx = 0

For ($i=0; $i -lt 10 ) {

$i++

Write-Host "Processing run" $i

$RPSResult = Measure-Command { $MbxRPS = Get-Mailbox -ResultSize Unlimited -RecipientTypeDetails UserMailbox | Select DisplayName, ProhibitSendReceiveQuota, WhenCreated, WhenChanged }

$MbxSec = [math]::round(($MbxRPS.Count/$RPSResult.TotalSeconds),2)

$Result = "RPS took " + $RPSResult.TotalSeconds + " seconds (" + $MbxRPS.count + ") mailboxes: averaging " + $MbxSec + " mailboxes/second"

Write-Host $Result

$TotalSeconds = $TotalSeconds + $RPSResult.TotalSeconds

$TotalMbx = $TotalMbx + $MbxRPS.Count }

Write-Host "Total runs: " $i

Write-Host "Total mailboxes: " $TotalMbx

Write-Host "Total seconds: " $TotalSeconds

Write-Host "Avg Mbx/Sec: " ([math]::round(($TotalMbx/$TotalSeconds),2))

# REST cmdlets return DisplayName in minimum property set and ProhibitSendReceiveQuota in the Quota set

$TotalSeconds = 0; $TotalMbx = 0

For ($i=0; $i -lt 10 ) {

$i++

Write-Host "Processing run" $i

$RESTResult = Measure-Command { $Mbx = Get-ExoMailbox -ResultSize Unlimited -RecipientTypeDetails UserMailbox -PropertySets Quota -Properties WhenCreated, WhenChanged }

$MbxSec = [math]::round(($Mbx.Count/$RESTResult.TotalSeconds),2)

$Result = "REST took " + $RESTResult.TotalSeconds + " seconds (" + $Mbx.count + ") mailboxes: averaging " + $MbxSec + " mailboxes/second"

$TotalSeconds = $TotalSeconds + $RESTResult.TotalSeconds

$TotalMbx = $TotalMbx + $Mbx.Count

Write-Host $Result }

Write-Host "Total runs: " $i

Write-Host "Total mailboxes: " $TotalMbx

Write-Host "Total seconds: " $TotalSeconds

Write-Host "Avg Mbx/Sec: " ([math]::round(($TotalMbx/$TotalSeconds),2))

In Figure 1 you can see the script chugging away to fetch 15,003 mailboxes and results being generated.

The overall results of this test are shown in Table 1.

Total mailboxes fetched in 10 runs: 150,030 (the Remote PowerShell commands failed on the 10th run and only processed 149,753 mailboxes.

| Total Seconds | Average mailboxes per second | |

| REST | 871.848086 | 172.08 |

| Remote PowerShell | 2188.1133701 | 68.44 |

Table 1: Comparing the performance of REST and Remote PowerShell cmdlets

Results are even more impressive when you combine REST cmdlets. For instance, fetch a set of mailboxes with Get-ExoMailbox and pipe them to Get-ExoMailboxStatistics to report mailbox sizes. More information is available in my theater session about these cmdlets recorded at Microsoft Ignite 2019 and a follow-up post with the scripts I used in that session.

Your mileage might vary depending on the code you write, but it’s obvious from my tests that the REST cmdlets are much faster than their Remote PowerShell counterparts.

A Slight Pause

As you start to work with the REST-based cmdlets, you might notice that the first time you run a cmdlet against a set of objects, it’s not quite as fast as you might expect. The impression is especially strong with small sets of objects (under a hundred or so). The initial slowdown is because the cmdlets support pagination, so when a cmdlet begins to process a set of objects, it sorts the objects to allow the cmdlet to resume processing from a retry point should the need occur. During this period, the cmdlet is also evaluated against RBAC. I call this the “warm up” phase, and once it’s finished, access to the objects is fast and robust. You don’t notice this happening when dealing with large sets of objects because the time used to paginate is a much smaller percentage of the overall run.

The Effect on Scripts

All of this is goodness but moving to the REST cmdlets is not a simple matter of upgrading scripts to use the new cmdlet names. Here’s my list of upgrade steps:

- Make sure that you connect to the Exchange Online REST endpoint by running the Connect-ExchangeOnline

- Change the cmdlet names from old RPS names to new REST names. For example, Get-Mailbox becomes Get-ExoMailbox.

- Check the Identity parameter. Remember those tweaks to use Azure Active Directory. The REST cmdlets support the object identifier (ExternalDirectoryObjectId) or User Principal Name for a mailbox, both of which are highly efficient for lookups against Azure Active Directory. Other PowerShell modules like Teams and Azure Active Directory already limit identities to object identifiers and user principal names.

- You can continue to use Alias or DisplayName as identities via the ANR parameter, but these lookups will be slower. For example: Get-ExoMailbox -Anr TRedmond

- For best performance, only request the properties you need to process. The REST cmdlets use the concept of property sets to group properties together into collections that are commonly processed together. You’ll always get the minimum property set returned. For example, if you want to work with mailbox quotas, you’ll specify that you want the Quota property set in a call like this:

$Mbx = Get-ExoMailbox -RecipientTypeDetails UserMailbox -ResultSize Unlimited -PropertySets Quota

If you need specific properties from a set, specify their name like this:

Get-ExoMailbox -AuditEnabled, WhenCreated, WhenChanged

If you want every available property, fetch the All property set.

Get-ExoMailbox -PropertySet All

- Check that all the parameters used in your script are supported by the new cmdlets.

- The REST cmdlets don’t respect the user locale for date formatting. You might have to format dates returned by the cmdlets if you want them to look nice in reports. A smaller gotcha is that the REST cmdlets return data ordered alphabetically while the older cmdlets order objects by creation date. This might affect how scripts work.

- Use piping whenever possible to take advantage of the multi-threading built into the REST cmdlets. Unfortunately, in most instances, if you want to manipulate or generate data about objects in the pipeline a ForEach loop is necessary.

- Check your performance after upgrade. Hopefully you’ll be pleased. You should see at least a 2x-3x performance increase over equivalent RPS cmdlets.

- Test, test, and test again to ensure functionality of the script is as expected.

Moving Ahead to the Graph

Now that Microsoft has started to upgrade Exchange cmdlets to use REST protocols, will they introduce a Graph endpoint for Exchange management? According to Microsoft representatives at the Microsoft Ignite conference, “it’s on our backlog and we’re investigating the work that needs to be done.”

The priority is to complete the work on PowerShell because that will have a direct and beneficial impact on customers, especially those working in large-scale enterprise tenants. Of course, given the amount of PowerShell Microsoft uses to manage its own tenant, they’ll gain too. And that’s not a bad thing.