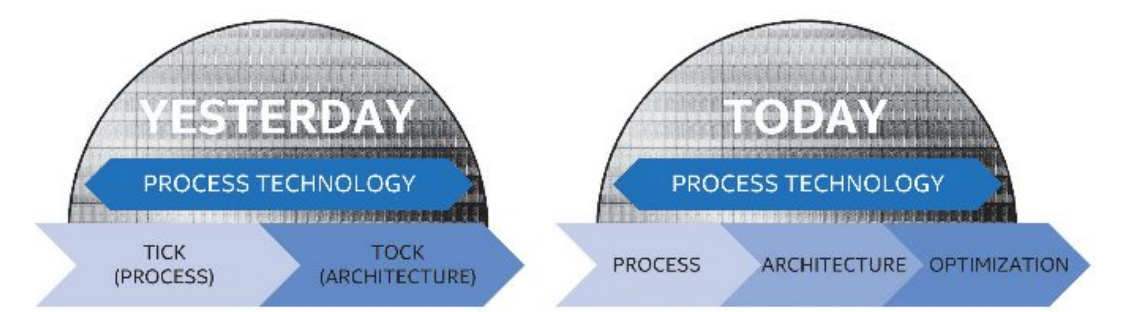

Stung by its failure to maintain long-held processor development techniques, Intel has declared that the era of “tick-tock” is over, to be replaced by a slower-moving methodology it calls “Process-Architecture-Optimization.”

The change was officially communicated in an Intel 10-K filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and was first reported by The Motley Fool.

For the uninitiated, Intel has been on its tick-tock processor development schedule for several years, with major releases—called “ticks”—interspersed with minor releases, called “tocks.” The schedule was similar to the one Microsoft used with Windows Server, where the minor releases were branded with the “R2” moniker.

Intel’s “tick-tock” schedule has been falling apart over the past few years, however, as the move to ever-smaller die sizes has proven more difficult and time-consuming that Intel had expected. For the most recent processor generation, called Skylake,” Intel had originally expected to move forward to a new “tick” release, called “Cannonlake,” that would usher in a new era of smaller 10nm manufacturing process. But it was forced to wedge in yet another “tock” release, called “Kaby Lake,” instead. Kaby Lake, like Skylake, will use the existing 14nm process, and will arrive in late 2016. And Cannonlake has slipped to late 2017.

But now, we know that the Skylake/Kaby Lake debacle is not be a one-off. And the “tick-tock” era is officially over.

“We plan to introduce new [microprocessor] architectures on a regular cadence,” Intel explains in its 10-K filing. “We expect to lengthen the amount of time we utilize for our 14nm and our next generation 10nm processor technologies, further optimizing our products and process technologies while meeting the yearly market cadence for product introductions.”

Looking at Intel’s own graphic depicting this change (above), one might refer to the new schedule as “tick-tock-tock,” but it’s possible that Intel doesn’t want to commit to always iterating “tick” releases twice.

Somewhat defensively, Intel argues that this new schedule will help it “continue making Moore’s Law a reality.” But the reality is that Moore’s Law—by which the number of transistors in integrated circuits has doubled roughly every two years—has also gone by the wayside. Intel admitted in 2015 that it had stopped keeping to this unofficial but widely-regarded law during the changeover from the 22nm to 14nm manufacturing process.

Intel’s argument is that other chip innovations will essentially allow it to continue providing the benefits of Moore’s Law while not technically adhering to its requirements.

“We have continued expanding on the advances anticipated by Moore’s Law by bringing new capabilities into silicon and producing new products optimized for a wider variety of applications,” Intel claims. “We expect these advances will result in a significant reduction in transistor leakage, lower active power, and an increase in transistor density to enable more smaller form factors, such as powerful, feature-rich phones and tablets with a longer battery life.”

As for the real-world schedule, Intel confirmed that its third 14nm product line, “Kaby Lake,” would still ship in late 2016, and that it would be followed by 10nm products. After that, Intel will turn to a 7nm process that, notably, will offer nearly identical transistor density to its 10nm products.