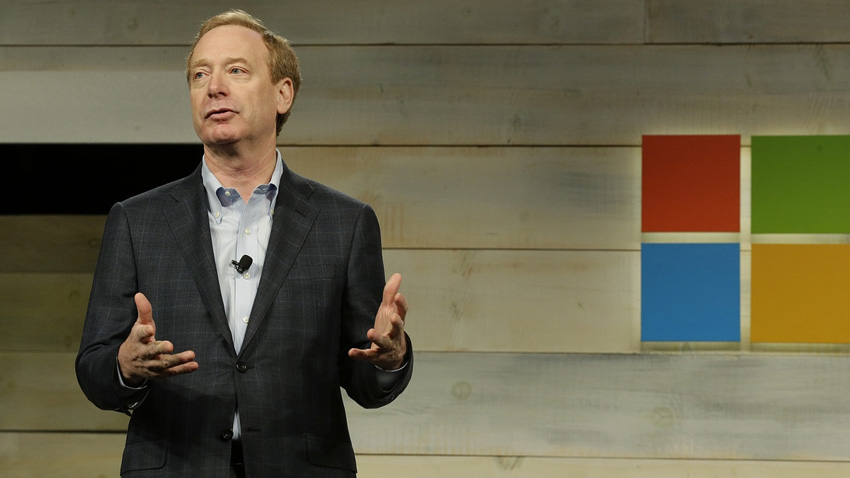

Microsoft Exec Testifies That Legal Conflicts Are Undermining Tech Gains

Microsoft President and Chief Legal Officer Brad Smith testified ahead of a U.S. Congressional hearing this week that conflicting and outdated international laws are hampering the tech industry’s ability to protect personal privacy and keep the public safe.

“The current legal trends are clear,” Mr. Smith testified. “Unless governments change course and adopt a new and more international approach, we risk confronting a conflict of law on steroids. This conflict should concern more than lawyers and people in the tech sector.”

(I was apprised of this testimony by a post in Computerworld.)

The issue, Smith explains, is two-fold. First, the laws that govern technology are old and outdated, and even the primary U.S. laws that directly relate to technology—like the electronic privacy law—are over 30 years old. And second, the laws that Microsoft and other tech firms must adhere to vary from country to country, and are often contradictory.

What’s needed, Smith says, is consistent and updated international standards.

“We need to establish a modernized approach that enables law enforcement to work with our allies to fight crime jointly by sharing evidence quickly and efficiently through clear rules,” he says. “It also needs to protect people’s privacy in accordance with new principles that recognize the importance of a person’s nationality and their right to be protected by their own law. We need new solutions that are international in nature and reflect the way that current technology actually works … new solutions that will work not only for technology, but for people.”

Smith cites some examples where international law enforcement cooperation has worked well—such as when the French government sought information stored in Microsoft’s servers in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, and the software giant was able to turnaround an FBI request in just 45 minutes despite the time change—but said such examples were the exception not the norm.

“Global companies must obey the laws and respect the rights of consumers and companies in each country where they do business,” he explains. “But because laws that are applied extraterritorially increasingly conflict with each other, a company trying to comply with the law in one country may be required to engage in actions that violate the law of another country.”

Consider a recent case in Brazil, which asserts its authority to compel U.S. tech companies to disclose the contents of users’ communications to Brazilian law enforcement, even when the data is located in other countries. Such action is illegal under the U.S. Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986—that 30-year old domestic electronic privacy law Smith referenced earlier—forcing Microsoft to make an impossible decision: Adhere to the law of Brazil, or break the law in the United States. So when Microsoft refuses to release information to Brazil, it is levied fines by that country.

Smith also noted the pending General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) in the EU, which would allow it to mandate cross-border transfers of personal data to and from Microsoft and other U.S. tech companies.

“This means that in the near future, EU laws effectively will prohibit us from transferring electronic communications that we store in the EU in response to unilateral legal process from most third countries, including from the Government of the United States,” he explained.

To modernize and standardize the rules that government how technology firms operate in the cloud computing era, Smith has specific recommendations for at both national and international levels. Here in the United States, the power to obtain digital evidence should be “grounded in due process and must be consistent with international law,” he says. And new laws should recognize the importance of a user’s right to be protected by the law of his or her own country. That last bit stands in sharp contrast to the stance of the U.S. government today.

“If a person is an American citizen or resident, their rights may be appropriately determined by U.S. law, and it seems appropriate for U.S. law to permit the extraterritorial and unilateral reach of a search warrant to that person’s data regardless of where it is located,” Smith argues. “But when someone is not a U.S. citizen and lives outside the United States, we need U.S. law enforcement to work in accordance with new international legal processes to strike the right balance between privacy and safety and avoid legal conflicts and international tensions.”

It’s just common sense. But getting common sense turned into law may take a bit more work.