Microsoft at 40

This past weekend, Microsoft moved into middle age, having reached the ripe old age of 40. Given the sweeping industry changes that have upended Microsoft’s position atop the personal computing market, there’s some cause for concern. But I’m not in the camp that believes that Microsoft’s best days are behind it. Indeed, looked at in the context of Microsoft’s full history, what’s happening now is simply a repeat of previous events.

In a letter to employees Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates—who essentially left the company but then returned last year as a part-time advisor to CEO Satya Nadella—explained why he was more focused on the future than the past.

“We have accomplished a lot together during our first 40 years and empowered countless businesses and people to realize their full potential,” he wrote. “But what matters most now is what we do next.”

The future has yet to be written. But the past has been well-documented, including the more recent 20 years of Microsoft’s history, during which I played an active role in observing and writing about the company professionally.

Here are some interesting facts and trivia about the company I’ve retained. Some of these are not well known.

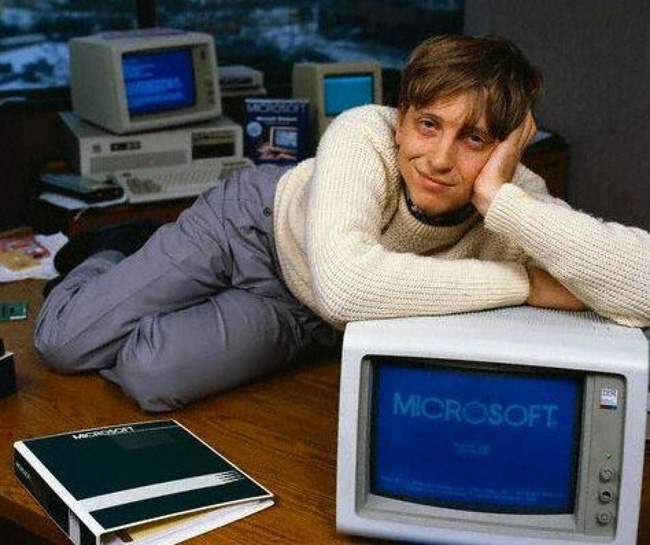

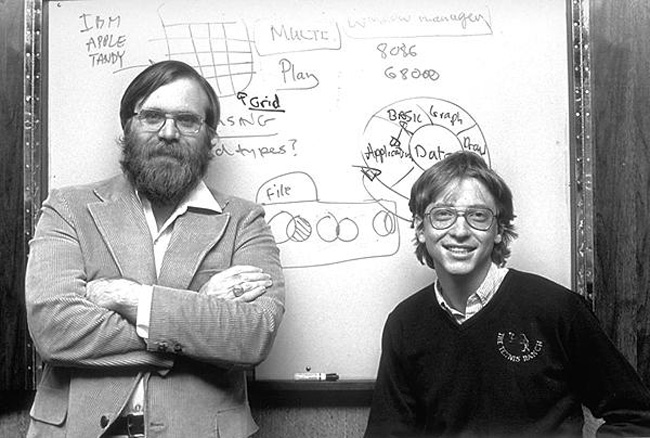

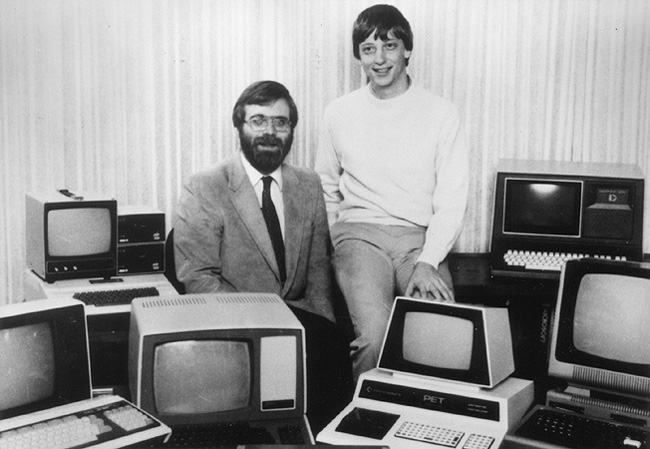

Founding. Microsoft was founded on April 4, 1975 by Gates and Paul Allen, and had a single purpose: Create and sell a BASIC interpreter for the Altair 8800, which many consider the first personal computer. Microsoft later adapted BASIC for many personal computing systems.

Hello from … Albuquerque? Microsoft was founded in dusty Albuquerque, New Mexico because that was the home of MITS, which made the Altair. It moved to Bellevue, Washington in 1979 because Gates wanted to be closer to home, and he felt that the dreary weather would keep his programmers indoors and working. Microsoft didn’t move to its current digs in nearby Redmond until 1986.

Why Microsoft. The name Microsoft is a combination of the terms “microprocessor” and “software”.

Microsoft’s first operating system wasn’t MS-DOS. In 1980, Microsoft expanded into PC operating systems by releasing—wait for it—Xenix, a version of UNIX that ran on—again, wait for it—the Digital PDP 11. Xenix was later ported to other hardware architectures, including of course IBM’s PC.

DOS was an accident. When IBM contacted Microsoft to produce an OS for its secretive PC project—the hardware giant was rushing the product to market and didn’t have time to create one itself—Gates suggested that they contact CP/M maker Digital Research instead. Stories about DR founder Gary Kildall infamously botching the negotiations aren’t exactly right—he was off on business and IBM refused to sign an NDA provided by Kildall’s wife—but the net result was the same: IBM went back to Microsoft and Gates reluctantly agreed to provide an OS.

Microsoft didn’t invent DOS. Faced with IBM’s rushed schedule, Microsoft didn’t have time to create an OS for the IBM PC either. So it licensed a CP/M clone called QDOS (86-DOS) from Seattle Computer Products for $25,000, renamed it PC-DOS, and tailored it for the PC. As it turns out, SCP didn’t just recreate CP/M, it allegedly stole some of its source code too. (This has never been proven, however.) But Kildall never sued because the laws were unclear, and Microsoft later purchased all rights to 86-DOS for just $50,000.

PC-DOS was not the only OS available for the original IBM PC. IBM also provided two other OSes with the IBM PC: CP/M-86 (yes, from Digital Research, though it shipped late and missed the launch) and the UCSD p-System, which was based on Pascal.

MS-DOS vs. PC-DOS. As noted above, the original IBM PC version of MS-DOS was called PC-DOS. But Microsoft’s single smartest decision, arguably, was insisting that it be able to license PC-DOS to other PC makers as MS-DOS. When PC clones from Compaq and other arrived—and reverse engineered the PC’s proprietary BIOS firmware—Microsoft was suddenly sitting on top of a windfall.

Compaq did the early compatibility work that made MS-DOS possible. Only recently revealed in Open: How Compaq Ended IBM’s PC Domination and Helped Invent Modern Computing (by Compaq co-founder Rod Canion), it was Compaq, and not Microsoft, that did the early and difficult work of making MS-DOS compatible with the many PCs variants out in the world. So Compaq actually licensed its modified version of MS-DOS back to Microsoft so that Microsoft could sell and license it to others.

Microsoft once gave up on Windows. Microsoft created early versions of Windows to counter easy to use graphical shells for MS-DOS. But with a partnership to create OS/2 with IBM—which wanted to reverse the mistakes of the PC past by taking the hardware and OS proprietary—Microsoft actually gave up on Windows for a time. Fortunately for the company, a small team was working on skunkworks improvements to Windows that let it work on then-new Intel 16- and 32-bit processors, and access more RAM and storage. Seeing this work, then-president Steve Ballmer ordered a bigger operation, and Windows turned into one of the most lucrative software offerings of all time. OS/2 was screwed, a fact that Microsoft hid from IBM for years, just in case.

Not just Windows. While most people think of Windows as the core of Microsoft, two other businesses—Server and Office—eventually established themselves as the equal of Windows from a revenues perspective, and in recent years both Server and Office have in fact been bigger businesses than Windows.

Internet Explorer was just like MS-DOS. Faced with a rush job to get its own web browser to market before Netscape established a web platform that might make Windows obsolete, Microsoft took a page from the DOS playbook: it licensed the source code for Spyglass Mosaic, the browser that formed the basis of Netscape’s browser as well. It then rapidly improved the browser and, after the initial release of Windows 95, bundled it in the OS.

Microsoft never wanted to make Xbox. Microsoft’s famous video game console only happened because Sega collapsed and stopped making its own hardware. Previously, Microsoft planned to let Sega take the risk on the hardware side and just supply OS and other software to those products. The Sega Dreamcast includes a Windows CE environment, for example, and the idea was that developers would be able to port games between Dreamcast and the PC easily.

NT 5.0 becomes Windows 2000. Windows NT 5.0 was originally seen as a superset of both Windows 98 and Windows NT 4.0, and would ship in both consumer and business versions and merge the codebases of the two product lines. That was a bit ambitious, so Microsoft held off on that work until Windows XP. But before that, it killed the NT brand, renaming the product to Windows 2000. And it released the interim Windows Millennium (Me) release for consumers, which was unfairly harangued on a number of levels despite introducing a number of technologies that would later be celebrated in Windows XP. Not the least of which was driver rollback.

Antitrust. Microsoft’s fall from grace was going to happen anyway—it’s too easy to rely on successful products rather than try to replace them with new businesses—but the software giant’s antitrust cases—especially in the US and Europe—helped hobble Microsoft at a crucial time and let companies like Apple and Google rocket to great success. Had Microsoft not be restrained by the US DOJ and European Commission during this “lost decade,” things might have turned out differently. Or not…

Technology problems. Concurrent to its antirust ills, Microsoft lurched from the failed Cairo project to the Trustworthy computing the Longhorn debacle, a one-two-three punch of internal ineptitude that taught Microsoft to stop biting off more than it could chew. These disastrous projects might have set back Microsoft years regardless. But when you combine them with the antitrust issues, it was deadly. Microsoft still hasn’t recovered. (And Windows 8 didn’t exactly help either.)

Reaction vs. innovation. Microsoft isn’t well known for leading the way to future technologies, though of course it has dabbled in such things as pen computing, tablet computing, touch computing and even holographic interfaces before many of its competitors. But Microsoft’s biggest successes have come from taking existing technologies—BASIC, command line OSes, GUI OSes, office productivity software and so on—and popularizing them by making them cheaper and more accessible. When you think about it, this is what Apple did more recently with iPod (MP3 player), iPhone (smart phone), iPad (tablet), and Apple Watch (smart watch), none of which were in their respective markets. Not being first is often a good strategy.

From servers to services. While many fret about Microsoft’s mobile devices fate, one could successfully argue that its server business-with a focus on the corporations that provide over two-thirds of Microsoft’s revenues—is far more important. And on that note, Microsoft’s transition from on-premises server and productivity offers to cloud services is one of the most successful software transitions in the history of computing. The future of Microsoft is in the cloud.

Multiplatform. Microsoft doesn’t get a lot of credit for its multiplatform work, but that’s mostly perception due to the overwhelming success of the PC/Windows duopoly. Before Windows hit it big, Microsoft ported BASIC, DOS, early productivity wares, and other offerings to multiple personal computing platforms. And even during Windows’ heyday, the firm ported NT and later Windows to other platforms like MIPS, PowerPC, Alpha, and Itanium and, most recently, ARM. Microsoft has simply gone where the money is, so its strategy today of supporting external mobile platforms like Android and iOS is in effect not all that new at all.

There’s so much more, of course, and a full telling of the Microsoft story would require a long book. Sadly, the current Microsoft era has been ill-served by such books, though of course there are many great choices from the early days and of course from the antitrust era of a decade ago. Hopefully, some more current Microsoft books will appear in the months and years ahead.